Hello Marko! It’s great to have you here on our Artist Spotlight. Could you please introduce yourself?

I’m Marko Djurdjevic, a veteran artist who’s somehow managed to survive about 30 years in entertainment. I started out in book illustration back in 1996, long before you could casually send a JPEG to a client for approval, and I’ve been going more or less non-stop ever since.

Over the years my work has spanned comic books, video games, film, TTRPGs, and collectible toys. I’ve collaborated with a long list of industry giants—Marvel, Sony, Warner Bros, Riot Games, Blizzard, Hasbro, Lionsgate, and plenty of others. Along the way, I’ve contributed to 200+ videogames, painted 350+ comic book covers during my exclusive run at Marvel, and helped shape more characters and worlds than I can realistically keep track of at this point.

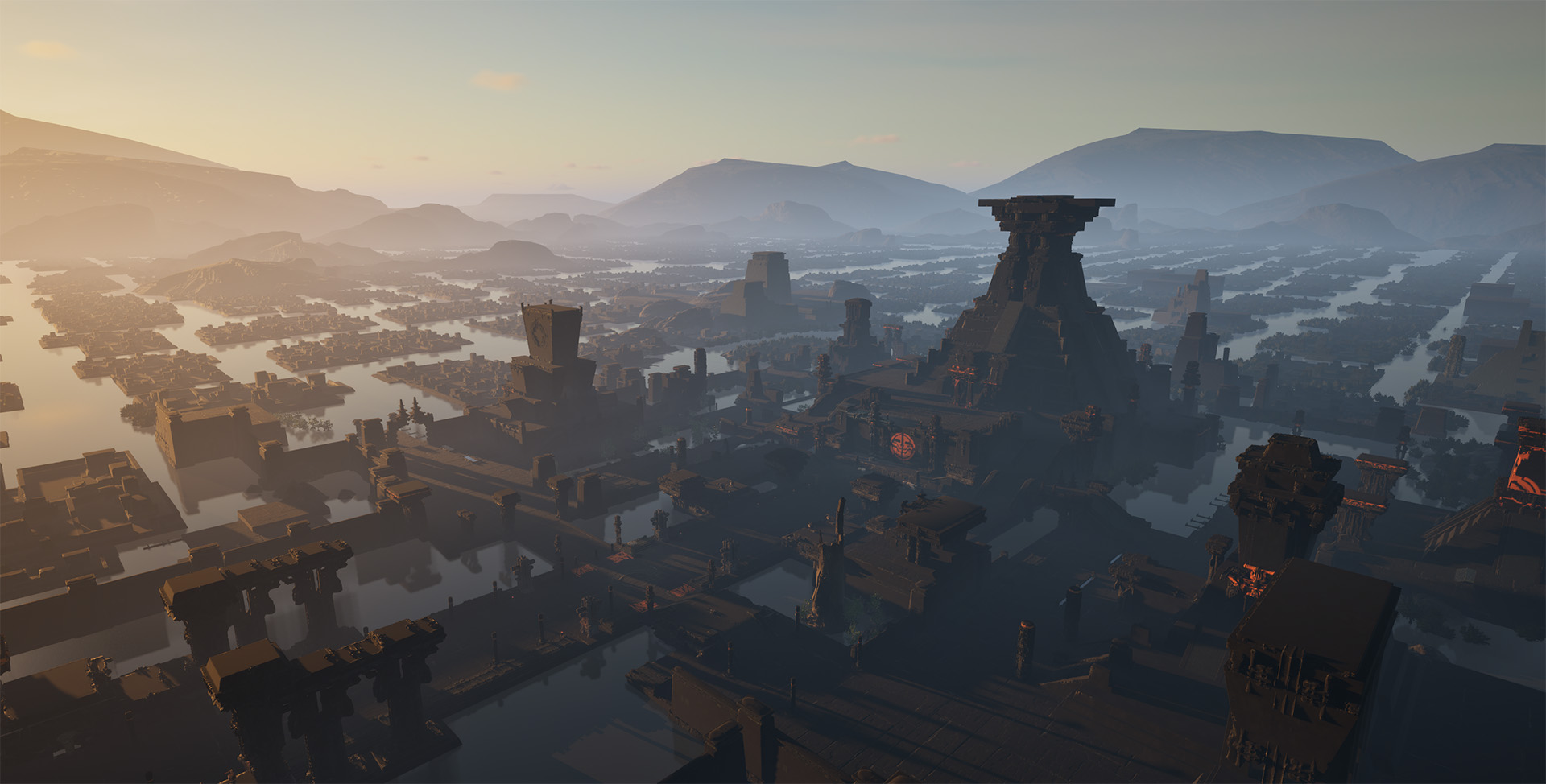

In 2010, I founded SIXMOREVODKA, a Berlin-based 2D art and visual development studio focused on early-stage concept work for videogames. Around the same time I created DEGENESIS, a transhumanist post-apocalyptic tabletop RPG that ran from 2014 to 2021, spawned over 20 publications, and developed a dedicated cult following.

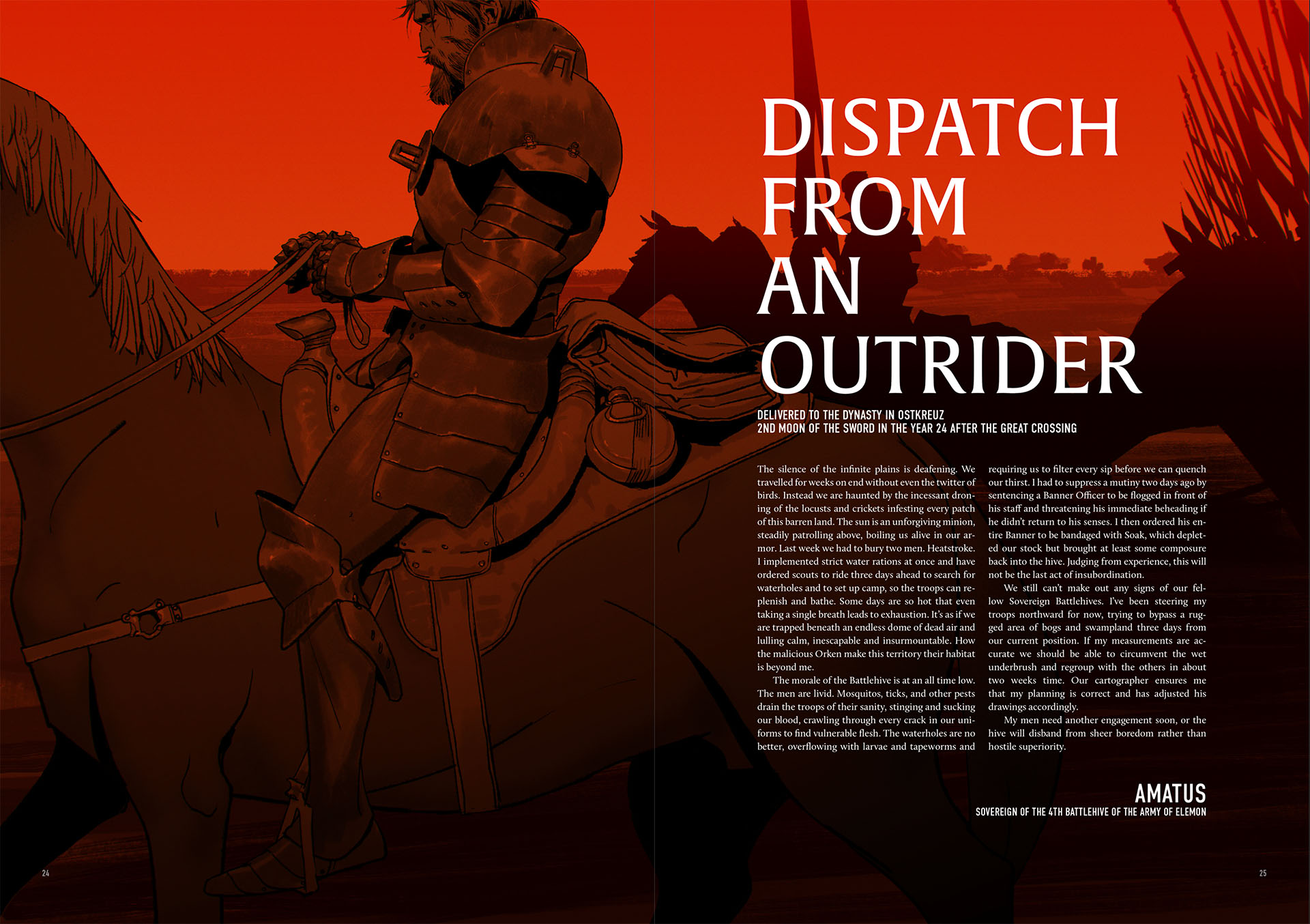

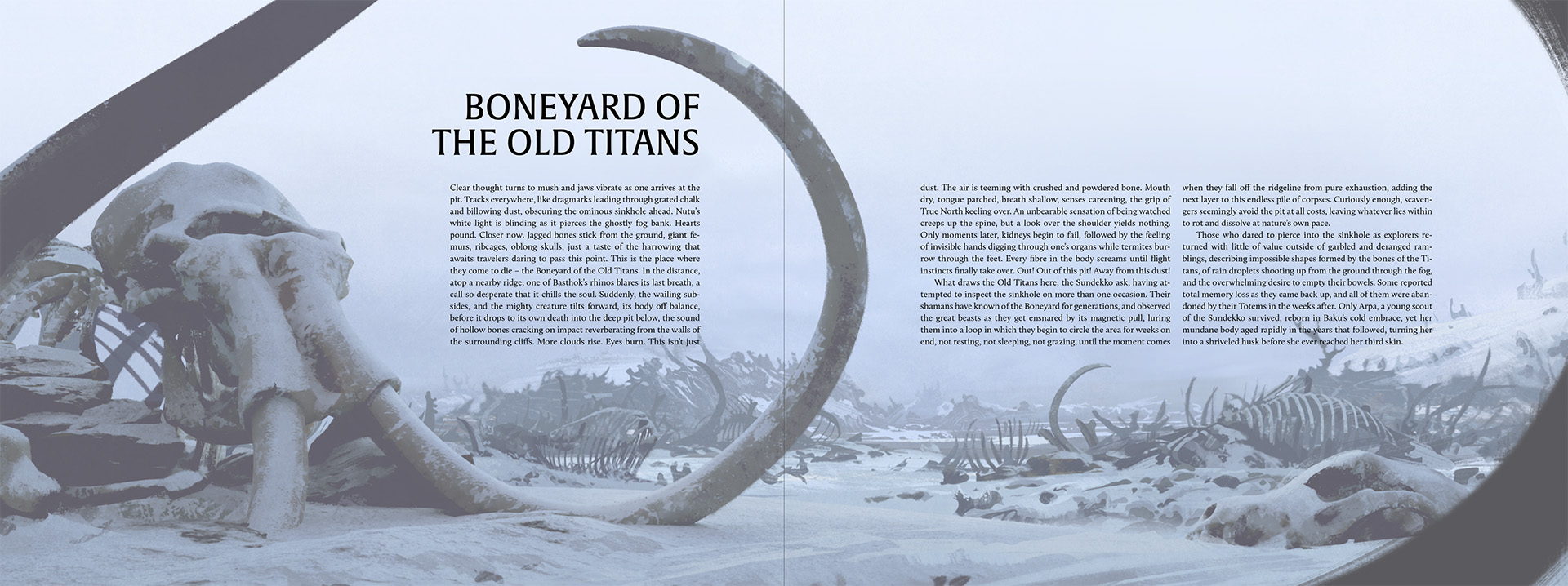

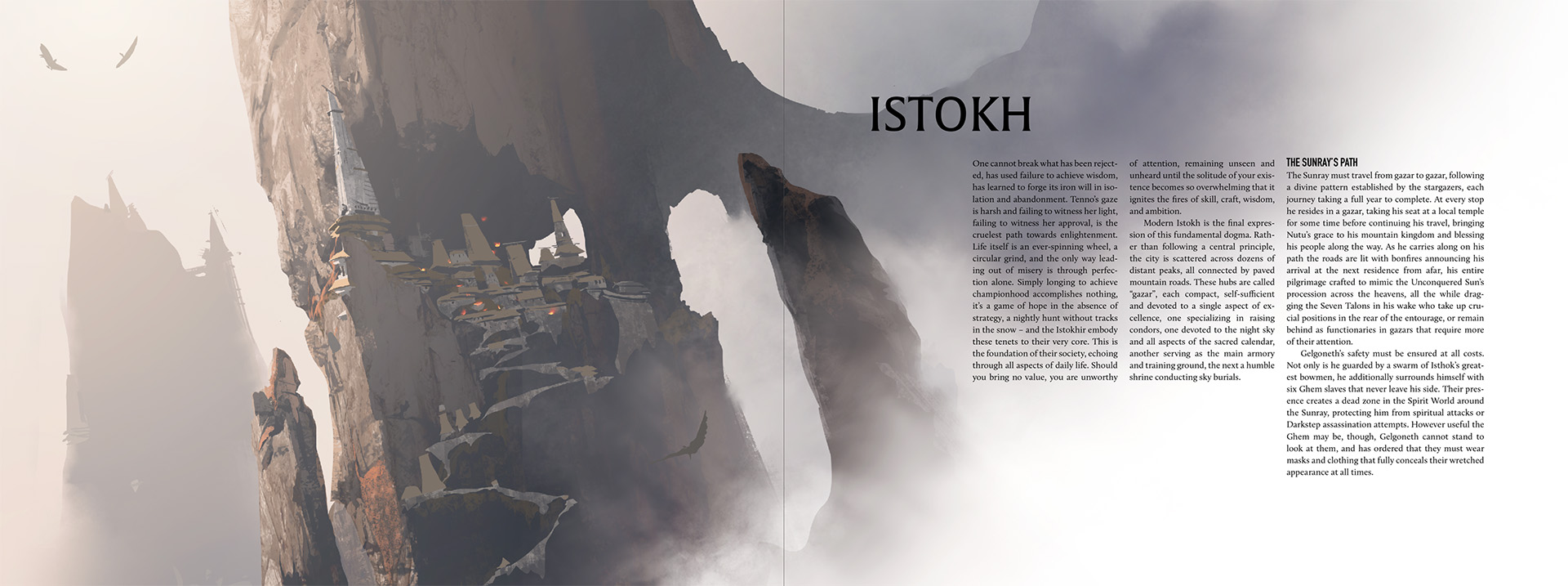

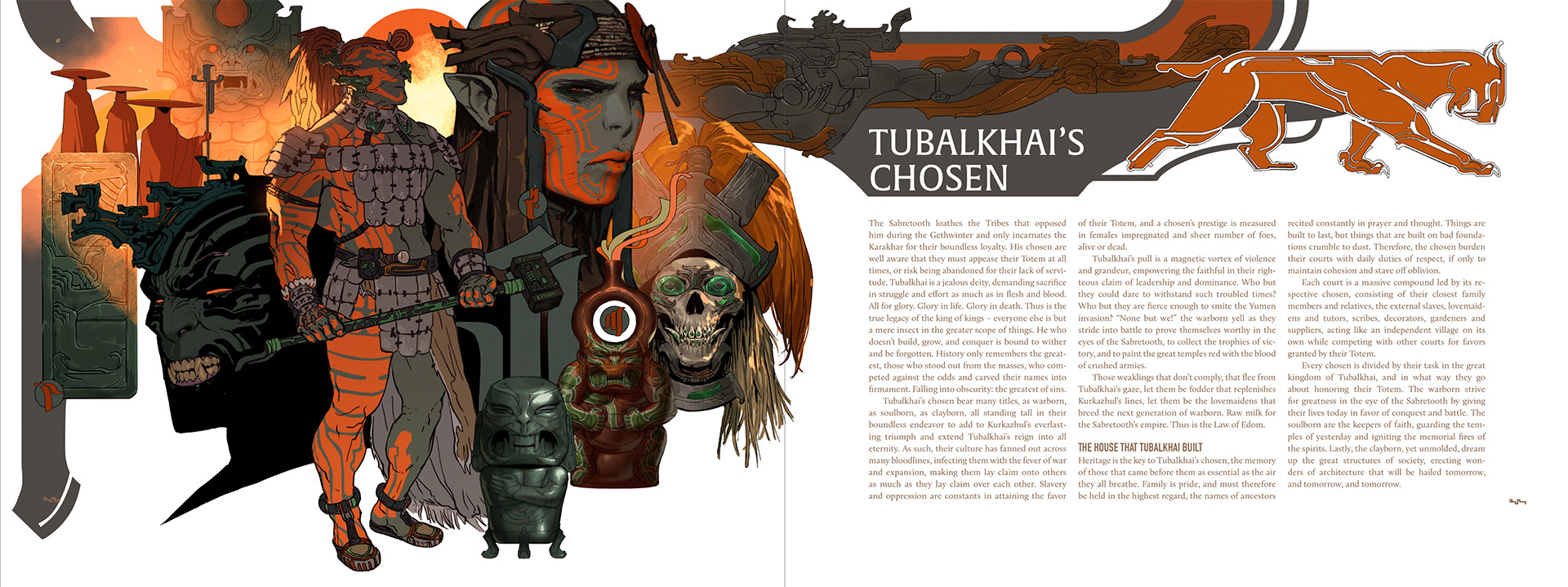

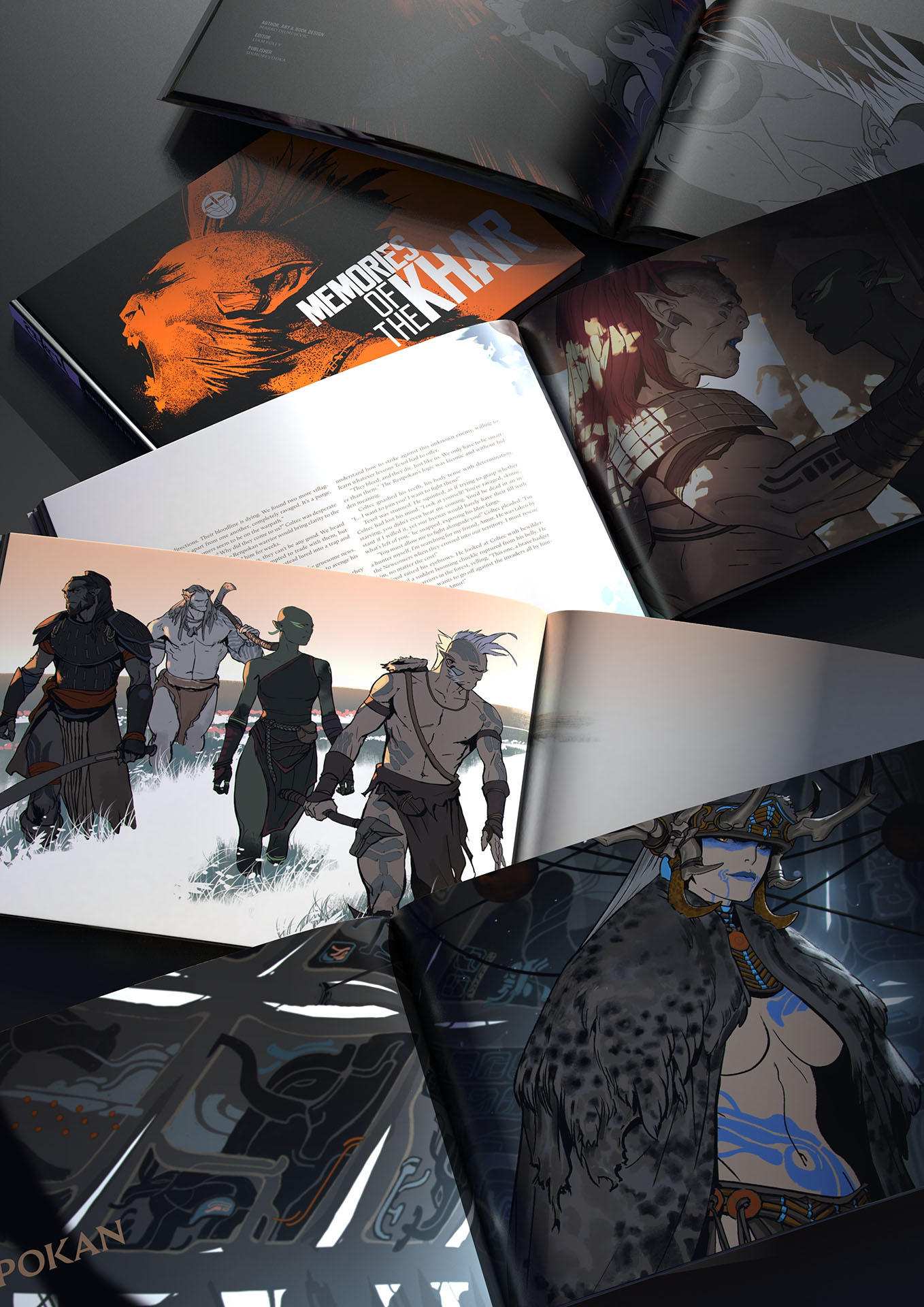

These days, my main focus is ORKEN: a creator-owned transmedia universe built to tell one ongoing epic narrative across multiple entry points—novels, setting books, graphic novels, and eventually videogames and other spin-offs. It’s easily the most complex project I’ve ever taken on. It’ll either become the thing I commit to for many years to come—or the graveyard of my ambitions. Either way, I’m enjoying the challenge. FOR NOW.

Marko, before ORKEN, before SIXMOREVODKA. When did you first realise you weren’t just making images, but building worlds?

I don’t know if there was a specific moment or some kind of sudden realization. Nothing that hit me from one day to the next. I think I’ve always just been drawn to things that belong together narratively.

Growing up with Marvel comics, everything existed inside the same universe. Characters didn’t live in isolation, storylines were interwoven, and events had consequences that carried forward and influenced what came next. That’s something serialized fiction does to you—especially when it’s at least somewhat canonical. It forces you to dig into past stories just to understand what’s happening in the present. That, more than anything else, is probably the core of where my fascination comes from.

Some people are perfectly happy to paint a single image or write one book and let that piece stand on its own forever. That’s a completely valid approach, but it’s never been enough for me. I can’t really commit to the idea that everything is said and done once one thing is finished. I always want to see what’s outside the frame—what led up to this moment, what follows after, and what the implications might be if the story keeps going.

It’s a more holistic way of thinking, where you’re considering things far beyond the scope of the original work. Not all of it is useful, and not all of it will ever be explained to an audience, but I find a lot of fulfillment in having followed a thought all the way to its termination point.

It's a very rich approach to exploring what lives beyond the frame. What does your world-building process look like today?

And how does that process change when you’re working alone versus collaborating with a team?

The process is actually rather simple and straightforward. First, define the core conflict. Then cement its cause and effect. The cause is the beginning of your story, the effect becomes your ongoing narrative. Once you understand the effect, you can also start thinking about its possible resolution — and by defining that, you’ve essentially discovered the end of your story.

At that point, you’ve built the skeleton of your world. Everything else is just connective tissue: filling in the gaps and refining detail within context.

This approach gives you a clear framework for what’s actually worth considering, and just as importantly, what can be cut. Anything that doesn’t serve cause, effect, or the eventual resolution is noise. I’m ruthless about that. If something exists purely as decoration, or to show off cleverness, it’s clutter — and clutter always gets in the way of the epicenter of an idea.

I have a particular aversion to worldbuilding that exists only on a conceptual level, where irrelevant details are spun out endlessly just to demonstrate that the author happens to be very knowledgeable about some obscure subject matter and desperately wants the reader to notice. That kind of indulgence does nothing for the story.

As for collaboration, my process is callously authoritarian. There is a vision from start to finish. I’ll listen to outside ideas, but I reserve the right of first refusal and I’m draconically strict about maintaining coherence. That doesn’t mean outside input isn’t valuable — quite the opposite. Being critical of other ideas often forces me to articulate why something works or doesn’t, and in that friction, better solutions tend to emerge.

This probably sounds arrogant, but it really isn’t. I’m my own harshest critic. There isn’t a single line I’ve ever written that I haven’t reread half a dozen times just to question whether it earns its place. I hate to bore my readers — and nothing bores them faster than fluff for the sake of fluff.

I don't think it sounds arrogant at all. You have something to say and you know how to curate that experience to best fit the story.

Which leads me to the next question. Authorship and Consistency are important factors to you in IP Development.

At what point does control stop being protection over the IP and starts to become a burden?

Control is the most important ingredient for authenticity. You can give it up early in hopes of broadening the appeal of your work and letting outside ideas flow freely into it—but that always comes with the risk of diluting what you actually set out to do. More often than not, you end up with something miserable: a creature trying to fart and hold it in at the same time.

Control only becomes a burden if your primary goal is mass appeal—if you’re trying to cast the widest possible net and please everyone. I find that approach intellectually dishonest. No matter what you make, there will always be people who dislike it. Universal appeal is a myth, and chasing it usually strips a work of the very things that made it worth doing in the first place.

Independence, to me, is about accepting that you’re not here to be loved by everyone. It’s about being attractive to a very specific audience instead. That’s where control stops being a limitation and becomes a form of clarity. You don’t have to ask what will sell before asking what you actually need to express.

If your work demands honesty, restraint, obscurity, edge—whatever feeds your soul—then those are the values you have to pursue. The right audience will trail along eventually. And if they don’t, at least you didn’t betray the thing you were trying to make in the first place.

Oh 100%. That is a very important ethos for art. But also for life in general.

I’d love to talk about your latest IP, ORKEN. First of all, congratulations on the video game trailer release and the upcoming books! It’s amazing to see this transmedia world come to life!

ORKEN lived in your head for nearly 25 years, correct? What kind of ideas survive that long?

The ones that survive that long are usually built around a very simple core conflict—so simple, in fact, that you keep wondering why nobody else seems to be touching it.

In most fantasy properties I can think of, conflicts rage on for millennia without either side making meaningful progress. The narrative only moves forward once someone gets turbo-buffed by some demonic, divine, or messianic force so the plot can finally advance. That inevitably leads to the same escalation of extremes: ever more powerful heroes and villains are introduced to keep the spectacle alive. It’s predictable, and frankly, a bit boring.

ORKEN deliberately dials the clock back to the very beginning. It’s about first contact between two peak civilizations that are hostile by circumstance, not history—and completely unequipped to understand one another. Instead of inherited grudges and ancient prophecies, it explores what happens when both sides make the wrong choices early on, and how quickly that leads to very real, very immediate consequences.

And that’s where things become interesting: First Contact is a narrow storytelling window where decisions are governed almost entirely by fear. Nobody has enough information to form grand strategies or long-term plans. Characters react instead of calculating, which makes them feel far more human. In a war that’s been going on for three thousand years, you eventually start asking yourself: “Why hasn’t anyone sent a fucking diplomat across that mountain range to talk with the Orcs?”

The longer enemies know each other, the more rigid a conflict becomes. Grudges calcify, strategies repeat, and outcomes turn into a simple numbers game—who can field more force and smash the other harder. But when time is short and intelligence is scarce, there’s a blanket that hangs over every action taken by an individual, a people, or an entire culture.

That blanket—that moment of uncertainty, fear, and irreversible choice—is ORKEN’s secret sauce.

Fear plays a central role in ORKEN. Fear of extinction, fear of the other, fear of being replaced. Which of these fears feels the most personal to you?

None of them, really. For me, it’s always been the fear of not belonging. I’ve spent most of my life trudging along as a lone wolf whose greatest claim to fame will be to die alone one day. I don’t operate well in groups, I despise ideology, and I have zero tolerance for larping a version of myself just to make others feel comfortable. That stance comes at a cost, and in the form of a long and empty road, with very few people you can genuinely confide in.

There’s a reason both my wife and my son label me autistic and awkward, and why I tend to get shoved into the basement when we have guests over—mostly to prevent me from accidentally insulting someone with my brash behaviour.

Hahah! It comes back to what you were saying before. Authenticity. Being a lone wolf who only confides in the few has its own set of advantages.

Whether its knowing who to trust or even simply peace of mind.

The fantasy genre is traditionally known for having a strong contrast between good and evil. However, you seem to deliberately avoid moral binaries in ORKEN.

Do you distrust clear heroes and villains?

I don’t distrust clear heroes and villains as much as I distrust the idea that good and evil are still useful categories. They don’t really hold up against reality anymore. Which is a shame—because it would be glorious if they did. All the good guys could just band together, stuff the evil ones into a rocket, and fire them into space. Problem solved.

But that’s not how the world works. Our own history is essentially an endless chain of stories about the “good guys” defeating the “baddies”, which is already quite suspicious. If good keeps winning consistently, you eventually have to ask: “How good were these people, really?

Once you go down that rabbit hole, you’re forced to confront perspective. What one side labels as evil is almost always defined by its own flawed moral framework, shaped by context, fear, and self-interest. From there, it becomes obvious that “good versus evil” is usually just hindsight storytelling—history written by whoever got to frame the big narrative last.

That realization is what drove the approach in ORKEN. Instead of handing the audience a moral compass and telling them where to stand, we deliberately explore both sides of the conflict in depth. Orcs and Humans each get the space to justify themselves, to be wrong for understandable reasons, and to act under pressure and out of fear rather than cartoon villainy.

The goal isn’t to replace one moral binary with another. It’s to give readers enough perspective to think for themselves—and to arrive at their own conclusions without being dragged there by the author’s biases.

Heroes and villains have historically played an important role in culture, literature and art. Reflecting our values, fears, and ideals.

Do you think we need them less as we grow older?

That’s a philosophical question, and it really depends on how you define a hero or a villain—and what purpose those labels serve relative to your own moral goalposts.

Is an action heroic in itself, or does heroism also apply to restraint and inaction? Where does stoicism fall on that scale? At what point does something become villainous, and by which parameters do we measure it? Can villainy be redeemed? Can a villain act heroically—and if so, what does that make them? An anti-hero? An anti-villain? Something else entirely?

The deeper you dig into those questions, the more fragile and contrived the labels start to feel. They stop reflecting reality and turn into convenient shortcuts. And once that happens, the characters built around them tend to become shallow—defined less by who they are and more by the box they’re expected to sit in.

I don’t think we necessarily need heroes and villains less as we grow older. I think we simply become less satisfied with them as fixed concepts. What we’re really drawn to over time are contradictions, tensions, and unresolved questions—because that’s what actually moves people.

That's a great philosophical answer, and I'll give it some proper thought.

How much of a storyteller are you, alongside being an artist? And how symbiotic is the relationship between those two roles for you?

I’d say I’m far more a storyteller than an artist. Art on its own doesn’t really satisfy any of my creative cravings. Finishing a piece that doesn’t belong to a larger narrative structure gives me very little sense of accomplishment. Art for the sake of art has always felt like spectacle to me—eye candy designed for a fleeting moment, but without much lasting resonance or depth.

That’s purely in relation to my own work. I can be deeply moved by the commitment and intent behind someone else’s art, and there are plenty of images that are permanently burned into my memory. I just don’t have that kind of emotional attachment to things I’ve created in isolation.

Novels are an especially intimate art form, often revealing parts of the author that other media cannot.

Are there aspects of yourself you’re only willing to reveal through writing?

I’ve been following the principle of “write drunk, edit sober” for many years now, and I still find it to be the most liberating way to actually finish a novel. Not because it unlocks some dark, rotten, and unspeakable truth I can’t express otherwise, but because it shuts down the constant overthinking that comes with sobriety—along with internalized habits like being polite, decent, and tactful.

Writing needs to be raw, honest, upfront, unhinged, and ultimately precise. Alcohol, for better or worse, lowers the guard just enough to get past self-censorship and into something that feels genuine. My inner grump tends to surface after the third vodka tonic, and that’s usually a pretty productive headspace to be in when you’re staring at a dirty keyboard late at night. Yes. I stare at my keyboard when I type.

That's the honesty the story deserves! Love it.

At Blauw Films, we’ve noticed that creating an independent IP today requires being over-prepared. Story, characters, visual language, business strategy and even future deal-flow. Is this level of preparation a core part of ORKEN’s ongoing development?

I’m not sure I fully agree with that statement. At its core, an IP is still a consumable product. How large it becomes—and how much can be spun off from it—depends entirely on its purpose and scope. It’s perfectly valid to start with something small and self-contained and let it grow organically over time.

So I don’t think being over-prepared is the key factor. What matters more is deciding what needs to be in place for the IP to feel complete at the moment you present it. That threshold is different for every creator. Some projects only need a strong premise and a clear voice. Others demand far more structure from the outset.

The way we’re approaching ORKEN isn’t meant as a blueprint for anyone else. In fact, I wouldn’t even claim it’s particularly healthy or sustainable in the long run. It has less to do with best practice and more with my own tendency to overachieve and overcommit. This is simply the level of preparation I need to feel comfortable releasing something into the world.

Yes, that is true. The scope of the IP totally defines how much preparation is required. When it comes to scope, you’ve chosen stylization based on restraint in a market that rewards spectacle.

Was this primarily an artistic or a production choice to streamline the process?

Both.

On a practical level, the stylization of ORKEN massively improves output. With this approach, I can produce five meaningful assets in the time it would otherwise take to finish a single, heavily rendered illustration. That matters, because worldbuilding only really comes alive once you’re able to pelt an audience with hundreds of visual markers. Especially for people unfamiliar with the universe, volume and consistency are far more important than isolated moments of polish.

But restraint isn’t just a production shortcut—it directly serves the emotional impact of the story. When you strip away hyper-realism and over-rendered detail, the imagery stops competing with the narrative. The art becomes suggestive rather than stealing the show, leaving space for the words to do the heavy lifting. If done right, the story hits harder because the visuals aren’t shouting over it.

And finally, there’s a clarity component we’ve tested time and again. People with zero prior exposure to ORKEN can grasp its core ideas very quickly through simplified imagery, without needing excessive explanation or handholding. A restrained visual language lowers the barrier of entry. The simpler the entry point, the more bang for your buck.

When your producer brain kicks in, does it override the artist?

How do you know whether you’re making a pragmatic decision or are simply afraid of taking a risk?

If anything, I’m taking far too many risks—so I don’t think the producer in me is all that dominant. I honestly can’t remember the last time I made what you’d call a purely pragmatic choice. I refuse to recycle even a single piece of art, and I have a bad habit of constantly expanding on my own plans long after they should’ve been locked in place.

That said, there is a producer somewhere in my head. He keeps track of everything that’s happening at once, which is useful—especially since I’m often the only person with a full overview of the production chaos in front of us. That guy is essential just to keep things from collapsing entirely, but he has strict boundaries. When it comes to artistic vision, he has to shut up and sit in the corner. One job. Observe. Do not interfere.

Is there a compromise you know you will never make with the IP?

Yeah. I would never abuse the work to smuggle in some questionable ideology, impose dictated morals, or engage in any form of emotional manipulation disguised as storytelling. The moment an IP becomes a vehicle for preaching rather than exploration, it turns into propaganda devoid of integrity.

I’d also refuse to turn it into a joke, or dilute it into public property where everyone gets to run wild with it. ORKEN isn’t a sandbox for trend-hopping or collective vandalism.

Your team trusts your gut, but when doubt enters the room, where does it usually come from?

The work, the market, or from within?

Doubt is always there—and it should be. It has its purpose. Doubt exists to drag you back to the drafting table and force you to surgically examine your own arrogance and bias. You need to be riddled with doubt to do any meaningful work. If you’re incapable of asking yourself, “Is this really the best I could have done, or can I do better?” then you probably shouldn’t be creating anything at all. You should go sell insurance instead.

The market, on the other hand, is largely irrelevant. Audiences can’t be predicted, and anyone claiming otherwise is full of shit. Most of that so-called insight is just cheap nostalgia math and low-effort bait designed to manufacture the illusion of retention.

What actually matters to people is whether the work feels honest. Whether YOU put the time in. Whether it’s not just another knockoff cash grab, but something that carries intent and conviction. Audiences are remarkably good at sensing when there’s a real soul behind a piece of work—and when there isn’t.

After having laid DEGENESIS to rest, how were you feeling in the period between that and Orken?

ORKEN had been burning under my fingernails for years. I postponed it repeatedly throughout Degenesis’ lifecycle, always prioritizing the existing TTRPG in an effort to keep that world alive. As a result, I never found the space to fully commit to something new. In fact, the first ORKEN novel, Field Reports from Edom, came together immediately after Degenesis ended. There was so much pent-up energy and momentum that wrote the whole thing in just nineteen days.

Ending Degenesis felt like an act of liberation. I had spent years trying to push the IP beyond its very dark, very niche audience, and at some point it became clear that it would never truly sustain itself. Year after year, I poured more into it than I ever got back—not because it made any sense, but out of a strange sense of responsibility toward the existing audience, who kept hoping the story would continue. That sense of obligation slowly ate away at my sanity and patience until only one question remained: “WTF am I doing this for?”

Once it was over I let out a long sigh of relief.

That's great to hear! Time to explore new grounds with a fresh burning fire.

What’s one belief the entertainment industry keeps repeating that you fundamentally disagree with?

That everything new has to be explained by pointing at something old.

“Oh, this book series is basically Game of Thrones, but darker.”

“This game combines the combat of XXX with the storytelling of ZZZ.”

It’s gross. Those kinds of buzzwords don’t clarify anything—they just create false expectations and overburden new work with baggage before it’s even had a chance to exist on its own terms. Referencing successful IPs like that always feels like a self-assigned pre-award, a way to shortcut legitimacy by association instead of letting the work speak for itself. It annoys the living fuck out of me.

And yes, we’ve had to resort to that language ourselves when talking about the ORKEN game. I disliked every second of it. Not because the references are inaccurate, but because that kind of claim-staking immediately narrows how people approach something new. Sometimes I wish it could just be as simple as: “Hey, this is a game we’ve been making. Do you want to check it out?”

That's truly one of the most counter-productive "habits" in the pitching process. And it never does the original IP justice.

You spent 25 years waiting until you felt “ready” to tell the story of ORKEN.

Tell me about that. What made you feel ready now?

I think a big part of it is a pretty serious case of imposter syndrome. I’ve never felt quite good enough. I tend to look at my own work and immediately think it’s too immature, too rough around the edges, too unrefined to be put in front of people. On top of that, I seem to have taken the concept of delayed gratification a bit too literally. If something didn’t have to go to market, it probably never would. I’d be perfectly content chipping away at it forever, chasing some imaginary point of perfection right before death.

The problem, of course, is that this is a completely broken way to do anything at all. You can’t meaningfully evaluate something while it’s still unfinished. Real reflection only happens once a piece is done and exposed to the world—everything before that is just speculation.

With ORKEN specifically, I always had the sense that I needed more time. Time to sharpen all the tools at once: writing, illustration, layout, product design. It’s a complex, interconnected beast, and I didn’t want to approach it half-assed. I also needed to reach a point where I could realistically commit the time and energy required to actually finish it, rather than letting it hover in permanent development limbo. That moment eventually arrived—and I’ve stretched it to its absolute limit.

If ORKEN outlives you and someone else one day inherits it, what do you hope they protect above all else?

Well, if I go the way of the Dodo at some point, the IP will eventually fall into my son’s hands and I already warned him not to pull a Brian Herbert on me.

Properties should be allowed to end with their creators.

An important message to the future.

Marko, as we're coming to an end of this interview, what kind of advice would you give to someone thinking of a career in IP Development? There is always a new generation taking their first steps into this adventure.

I think the world desperately needs new stories—and more importantly, stories that actually resonate with the times we’re living in. But it’s also becoming harder and harder to break through the wall of white noise that surrounds all forms of entertainment.

So my advice would be: start small. Think grassroots. Find your crew and your audience early, and grow alongside them. Let them participate, give feedback, and help carry the idea forward. These people aren’t just consumers—they’re your ambassadors, sometimes even your missionaries—and they need to be treated with respect and included in the journey.

The era of simply making something, dropping it online, and waiting for virality to strike is largely over. Attention is too fragmented, and trust is too scarce. What sustains projects now is a genuine relationship with the people who care enough to stick around. If you want longevity in IP development, don’t chase reach—build a community. Leverage your supporters, because in the long run, they’re the only real foundation you have.

Thanks so much for being a part of this Marko!

As always, we like to end the Artist Spotlight with a personal recommendation from the artist. Any good films, books, habits, or anything else you’d like to recommend to the reader?

Watch “There Will Be Blood” twenty-five times, and appreciate the fact that every single time it feels like the first. Drink. Smoke. Talk to yourself. Be your own worst critic, and only commit to things you genuinely believe in. If something doesn’t demand your full conviction, it’s probably not worth your time. And don’t kid yourself into thinking you can be rich, successful, and fulfilled without paying a price. You will sacrifice everything along the way— health, vacations, social life, hobbies, sleep, nerves, sometimes even your basic bodily needs. And that’s ok.

Explore the Artist Spotlight

[1]: Dreams of Blauw are any form of crystallised thought based on honest expression. Sometimes they linger a shade of blue in your after-image.