Why You Shouldn’t Write Like Tolkien (Unless You Are Tolkien) - Part I

The Life, Language, Myth, and Method of J.R.R. Tolkien

Blauw Films

In a Sarehole in the ground there lived a Tolkien. Not an oily, dirty, smoky hole, filled with rows of factories and a sooty smell, nor yet a muddy, lousey, foxhole with nothing in it to hide behind or to read: it was a Tolkien-hole, and that means…

What does that mean? What is it that makes a Tolkien-hole? England? God? Love? Loss? Language?

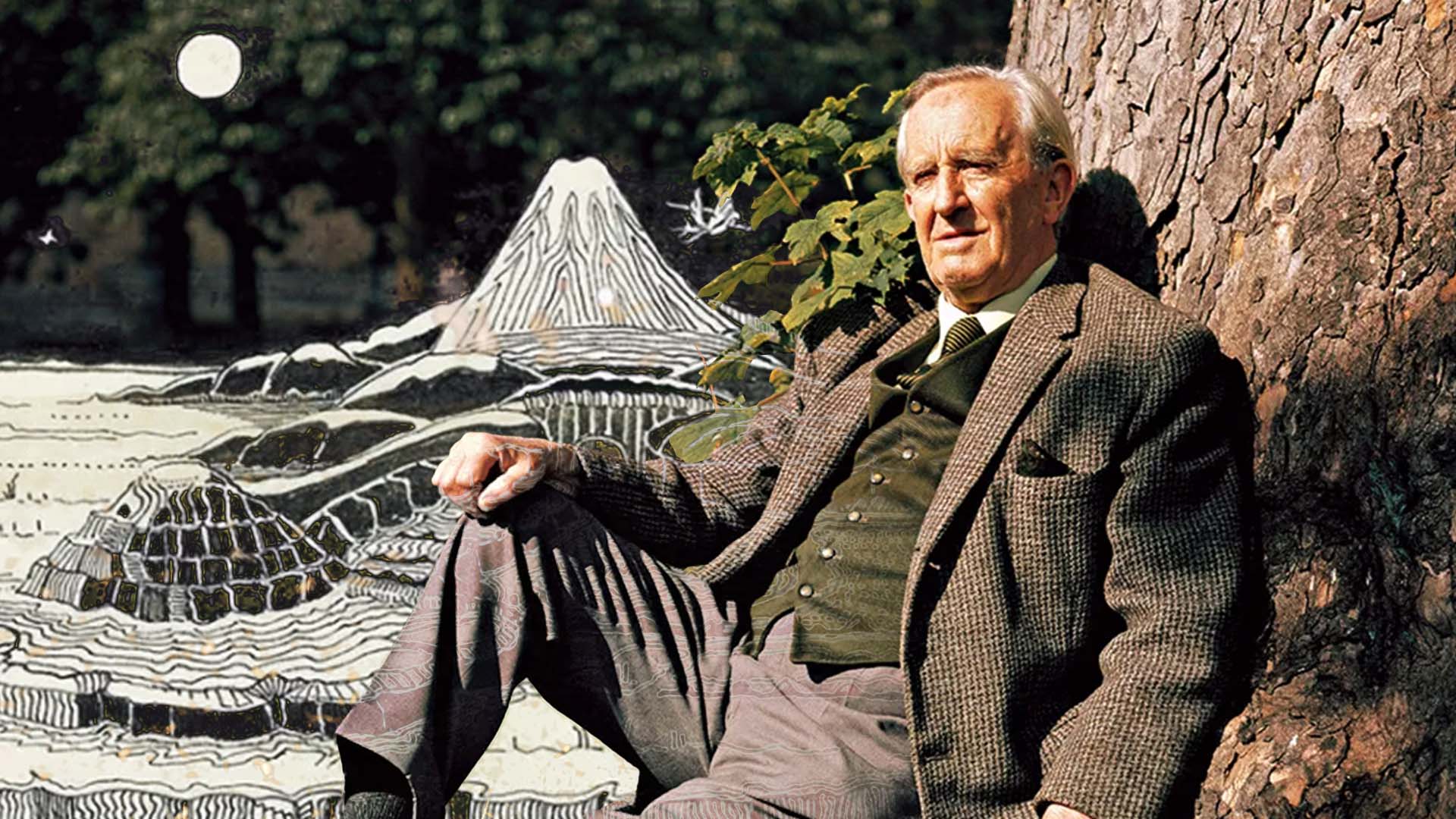

In the pantheon of modern literature, few figures cast a shadow as long as J.R.R. Tolkien. His influence on the fantasy genre is so total that most subsequent efforts, whether consciously or not, live in his shadow.

The question is: does Tolkien’s shadow darken or illuminate all it touches?

For decades, aspiring authors have attempted to replicate his epic tone — his invented languages, his maps, and his lore-laden leviathan of a world. But here’s the uncomfortable truth: unless you are Tolkien — unless you are, a devout Catholic scholar of ancient languages, a survivor of the Somme, an orphaned child of rural England touched by industrialisation, and a man who mourns the lost mythos of his homeland — you probably shouldn’t try to copy his unique approach to world-building.

Tolkien’s genius was born out of a lifelong obsession with language, myth, and morality. Tolkien’s imagined world — what he called a “secondary world” — was not the product of mere imagination, but the amalgamation of deep religious commitments, a profound love for linguistics, and a scholar’s grief over the lost legends of England. Tolkien’s life and process were so specific that to try to imitate his method without sharing his mind and experiences risks building a cathedral in a marsh made of mud.

And yet, as Humphrey Carpenter reminds us in J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography, even the facts of Tolkien’s life only take us so far. He writes:

‘...all this says nothing about the man who wrote The Silmarillion and The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, does nothing to explain the nature of his mind and the way in which his imagination responded to his surroundings. Certainly Tolkien himself would have agreed with this. It was one of his strongest-held opinions that the investigation of an author’s life reveals very little of the workings of his mind. Maybe; but before we abandon our task as utterly hopeless, we could perhaps move in a little closer than the viewpoint we adopted for the imaginary day, move in and observe, or at least hazard a few guesses about some of the more obvious aspects of his personality. And if after this we may not have any better idea why he wrote his books, then at least we should know a little more about the man who did write them.’ (pp. 166-167).

While Tolkien's work offers a soaring standard of what fantasy can be, most writers must focus not only on world-building — on the names, languages, and maps — but on the narrative, and the interplay between world and story. And to do that, one must let story and world evolve organically, each colouring the other without building one in the absence of the other.

To write like Tolkien, you would have to be Tolkien. But most of us are not — and in that recognition lies the path to better storytelling: your own path.

In this series we will examine what it takes to begin carving out your own path, but before we do that, we will look at what exactly a Tolkien-hole means.

And so we arrive at the inevitable question posed by Carpenter:

‘Where did it come from, this imagination that peopled Middle-earth with elves, orcs, and hobbits? What was the source of the literary vision that changed the life of this obscure scholar? And why did that vision so strike the minds and harmonise with the aspirations of numberless readers around the world? Tolkien would have thought that these were unanswerable questions’. (p. 342).

But answer them we will! Or at the very least we are going to try. Over a series of blogs will set out on our own epic quest to try and understand why J.R.R. Tolkien’s work is so definitive. We will examine his life. How love and death formed him. How language and mythology shaped him. How his work is viewed today, and ask whether it is truly inimitable, or whether there are lessons we, as writers paddling in the wake of ol’ Tollers, can take away from his life and, if he had any, his process.

But to do this we must begin not with Middle-earth, but with Middle England. For every mountain, and every forest in Middle-earth is deeply rooted in the soil of his life and the soil of a half-forgotten England.

Click here to join us in the real Shire and let the journey begin...

%20by%20Ivan%20Aivazovsky.jpg)

0 Comments