Why You Shouldn’t Write Like Tolkien (Unless You Are Tolkien) - Part II

The Morality Of Middle-Earth

Blauw Films

A Hobbit’s Tale: Part 1

The Seeds of the Shire: South Africa to Sarehole

The smell of fresh bread and clover drifted on the air. A quilt of soft green hills and golden fields stretched lazily to the horizon. Winding streams and babbling brooks wove amongst the neatly trimmed hedgerows. Wisps of smoke curled from the stone-stack chimneys and joined the picture book clouds as they drifted through the blue sky. Two boys walked arm in arm down a country lane. They were laughing. They were happy.

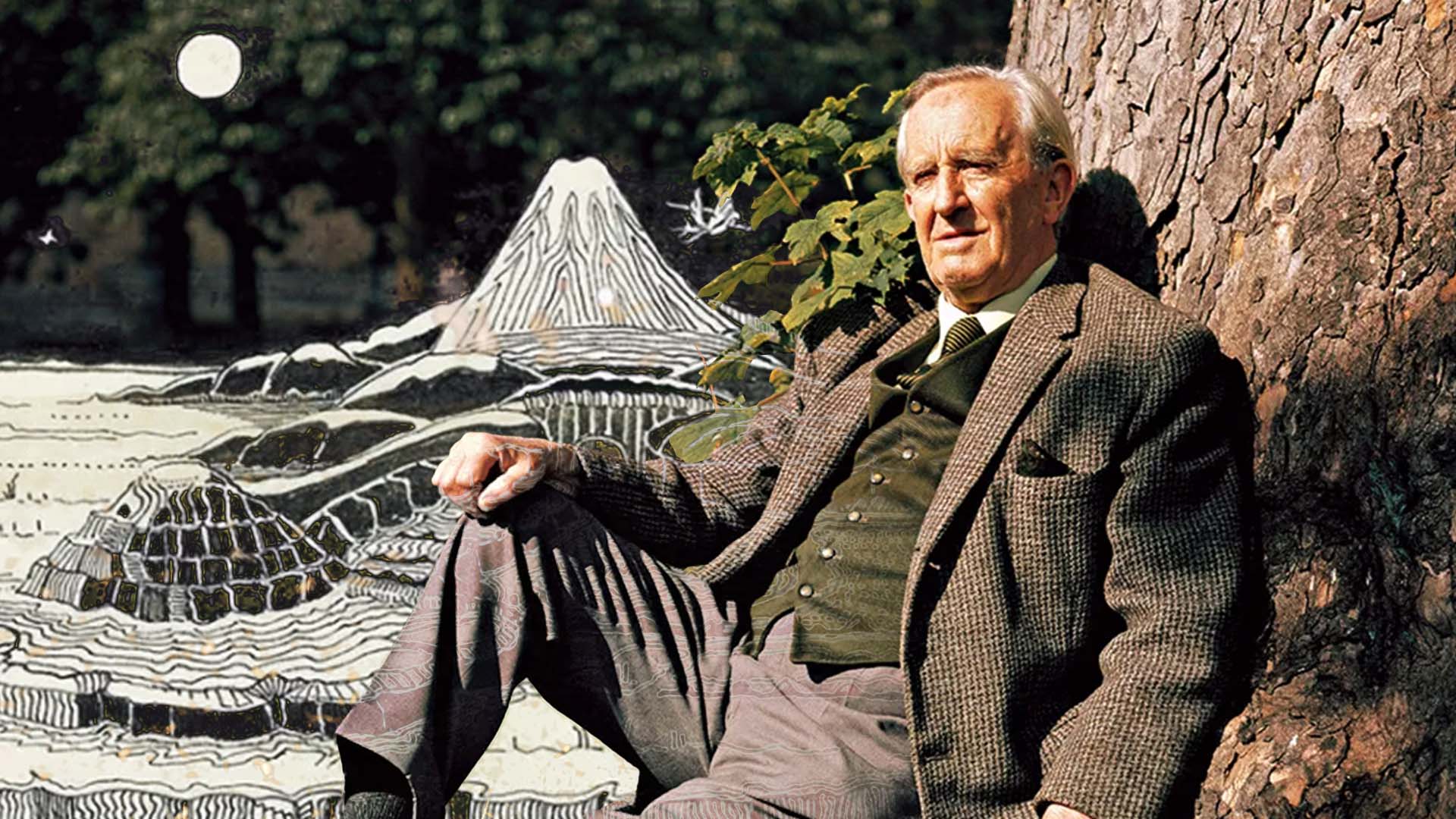

Years later one of those boys sat in a stuffy room in the Randolph Hotel in Oxford. He was no longer a boy. His face was lined and his hair was as white as the smoke seeping from the pipe resting familiarly in his cracked hand. He sat in a comfortable chair, one leg crossed over the over. He seemed at ease with himself, if not with the microphone balanced near by. He glanced with curiosity at the sweaty sound engineer, before drawing from his pipe again and settling a little deeper into the soft cushion, waiting, some what impatiently, for the young man sat opposite to ask his next question.

Deny Gueroult, or the chap from the BBC as the old man thought of him, cleared his throat, “Have you a particular fondness for these comfortable homely things of life that the Shire embodies: the home and pipe and fire and bed—the homely virtues?”

“Haven’t you?” The old man responded with a chuckle.

“Haven't you Professor Tolkien?”

“Yes, of course! Yes, yes, yes.” Tolkien replied as he stared into the unlit fireplace, a wistful look appearing in his twinkling eyes.

*

It was a fondness that ran deeper than Professor Tolkien's chuckle suggested. Those “comfortable homely things that the Shire embodies” were not invented to merely dress a fantasy world, they were a deep part of him, something he inherited from the life he had known as the boy walking arm in arm with his brother down that country lane on that golden day.

In 1958 Tolkien wrote: “I am in fact a hobbit, in all but size. I like gardens, trees, and unmechanised farmlands; I smoke a pipe, and like good plain food (unrefrigerated), but detest French cooking; I like, and even dare to wear in these dull days, ornamental waistcoats. I am fond of mushrooms (out of a field); have a very simple sense of humour (which even my appreciative critics find tiresome); I go to bed late and get up late (when possible). I do not travel much.’’

This list could have come from the pen of Samwise Gamgee himself (apart from perhaps the hatred of French cooking), but this hobbit, Mr John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, was born not in a snug hole in the Westfarthing, but in Bloemfontein, South Africa in 1892 to English parents. His very earliest memories were shaped by a climate and a landscape utterly unlike the England he would come to love. The sun was harsh, the air dry, the trees alien, and as he later recalled, “If your first Christmas tree is a wilting eucalyptus…” it leaves a mark.

Another indelible mark was left when young Ronald was four. His mother, Mabel, took him and his younger brother on a family visit to England. It was during this trip that devastating news came from across the seas: his father, Arthur, had died of a brain haemorrhage, caused by rheumatic fever, back in South Africa. Tolkien was left with only the faintest image of the man. As Humphrey Carpenter notes:

‘He had almost forgotten his father, whom he would soon come to regard as belonging to an almost legendary past.’ (p. 32).

Mabel, left suddenly a widow with two small boys, decided to remain in England. It was a decision that would shape her son’s imagination for life. She sought refuge and stability in a place that would prove to be his first true home: the small rural hamlet of Sarehole. Wyatt North in, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Life Inspired, describes its quiet simplicity:

‘Mabel was now dependent upon assistance from her family. She settled herself and the boys in the tiny hamlet of Sarehole, nestled amidst a bit of old forest not far outside Birmingham. The few houses of Sarehole hugged a road along which cows were driven to market in the city.’ (p. 10).

It was a hamlet caught between two worlds: the old England of hedgerows, streams, and craft mills, and the growing shadow of the industrial city just over the horizon. Carpenter captures the significance of this move:

‘The effect of this move on Ronald was deep and permanent. Just at the age when his imagination was opening out, he found himself in the English countryside.’ (p. 35).

For Tolkien, this was paradise. Wyatt North paints this picture:

‘Ronald’s lush new surroundings was particularly affecting, and he learned to love the English countryside deeply. Together with his younger brother—the two of them dressed in Little Lord Fauntleroy outfits with matching long hair—Ronald blissfully roamed the nearby Warwickshire countryside, a part of the West Midlands region. Its natural beauty, complete with thick woods, Moseley Bog, two mills with millponds, and flowered meadows and dells, would remain in his memory to be tapped periodically by his muse’. (p. 10).

It is worth pausing here, in this blissful moment of childhood, before the smoke of factories cloud the horizon. You can almost hear the River Cole murmuring to itself, smell the flour dust from the old mill, hear the shouts of the farmer (known as The Black Ogre), as he chased Ronald and his brother Hilary (their arms and pockets full of stolen mushrooms) as they escaped amongst the sun dappled elms.

Sarehole was Tolkien’s home, and one day it would become the model for the Shire. Its mill, its trees, and its quiet lanes, all came to form the idyllic homeland of the hobbits.Tolkien later made the connection explicit and described how deeply this landscape shaped him:

“The shire is very like the kind of world which I first became aware of things... just at the age of imagination opening up, to suddenly find yourself in a quiet Warwickshire village, I think it endears a particular love of what you might call central midland English countryside, based on a good wall of stones and elm trees and small quiet rivers and so on, and of course a sort of rustic people about.”

At the time Birmingham was still some way off, but not far enough. “Traffic was limited to the occasional farm cart or tradesman’s wagon,” Carpenter writes, “and it was easy to forget the city that was so near.” (p. 36). The second city of the empire, named as such due to its vast industrial output, lurked on the near horizon. An ever-growing beast, spreading its tentacles out into the countryside. The city’s approach was inevitable, and its arrival irreversible, and arrive it did.

Now it’s time to leave the Shire. To embark on the journey proper. To leave Sarehole and enter the mirky mists of a land far less desirable.

As Bilbo Baggins said, ‘It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door. You step into the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to’.

Click here to be swept off to... Birmingham!

.jpg)

%20by%20Ivan%20Aivazovsky.jpg)

0 Comments