Why You Shouldn’t Write Like Tolkien (Unless You Are Tolkien) - Part III

The Scouring of the Shire

Blauw Films

A Hobbit’s Tale: Part 2

Sarehole to Birmingham: The Scouring of the Shire

The smell of coal smoke and iron dust hung heavy in the air. A forest of red chimneys and factory stacks rose starkly against a grey horizon. Rail lines and canals cut across the city, threading past brick terraces and soot-stained walls. Smoke billowed and lingered, dimming the sun, as clattering wagons and rattling trams filled the streets with noise. Two boys hurried along the pavement, their collars turned up against the grime. They were quiet. They were far from home.

*

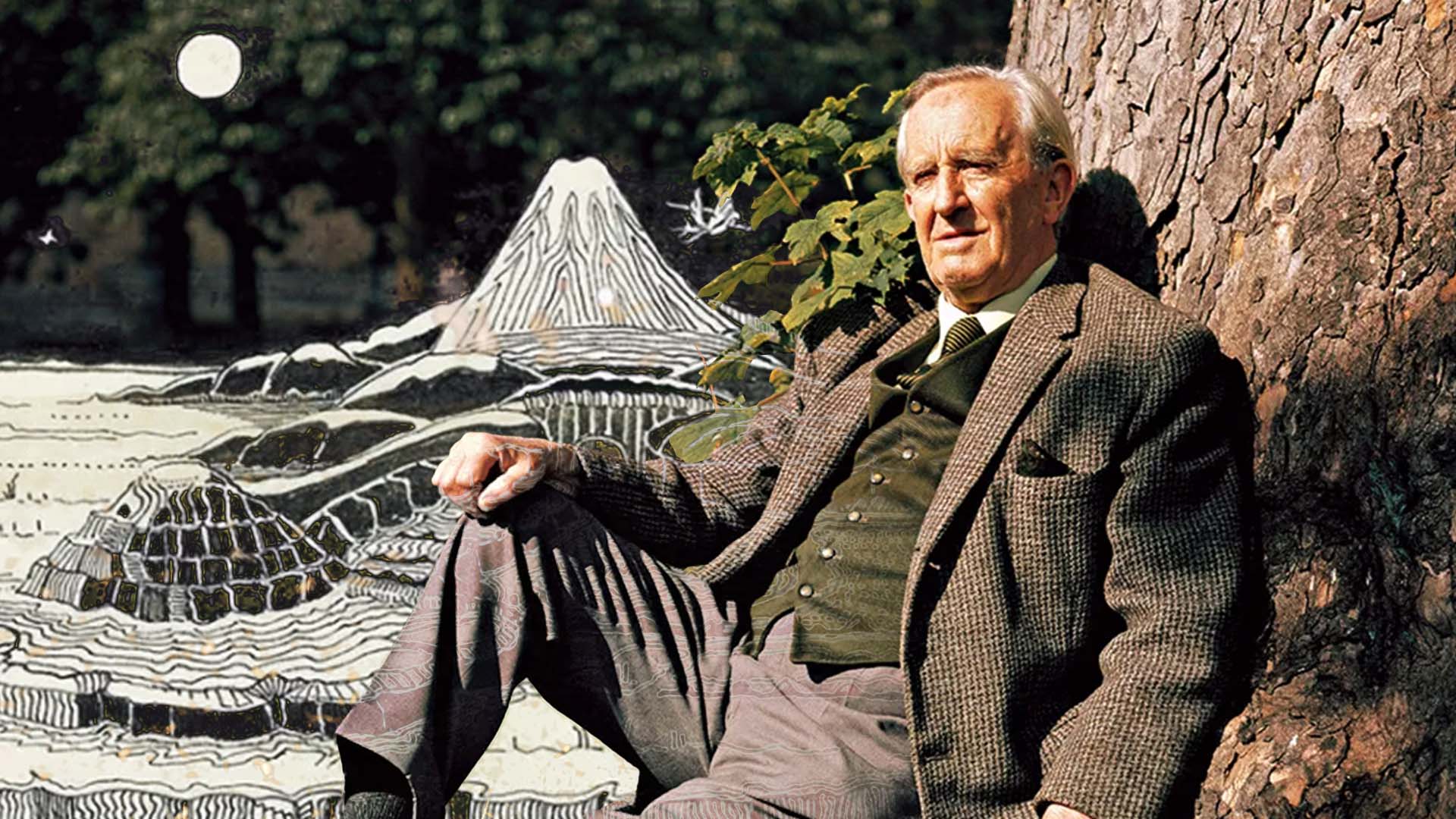

When industry began to seep into the Sarehole area, bringing railways and factories to the edge of this pastoral haven, all that Tolkien held dear was in peril. Carpenter sketches one small, telling image:

‘Over the road a meadow led to the River Cole, little more than a broad stream, and upon this stood Sarehole Mill, an old brick building with a tall chimney. Corn had been ground here for three centuries, but times were changing. A steam-engine had been installed to provide power when the river was low and now the mill’s chief work was the grinding of bones to make manure.’ (p. 36).

Tolkien saw it not just as a physical encroachment but as a spiritual loss. He later wrote:

“The country in which I lived in childhood was being shabbily destroyed before I was ten — in days when motor-cars were rare objects (I had never seen one) and men were rarer than sheep, and when practically every tree had a name and its individual tale.”

Soon industry poured into the heart of Sarehole, and now factories belched, motor cars roared, and the trees with names were felled to make space for more factories and more motor cars.

It is no coincidence that the scouring of the Shire, a chapter added near the end of The Lord of the Rings (and one absurdly omitted from Peter Jackson’s films), is one of the most mournful sections in the work. When the Hobbits return home, they find the Shire ruined: trees cut down, homes gutted, the Old Mill replaced with a looming factory, and a new authoritarian regime controlling everything from farming to beer:

“It was one of the saddest hours in their lives. The great chimney rose up before them; and as they drew near the old village across the Water, through rows of new mean houses along each side of the road, they saw the new mill in all its frowning and dirty ugliness: a great brick building straddling the stream, which it fouled with a steaming and stinking overflow. All along the Bywater Road every tree had been felled.”

This isn’t fantasy, it’s Sarehole. And it’s real. It is Middle England turned into Mordor by industrialism, bureaucracy, and greed.

Although, as we will discuss later, Tolkien turned his nose up at any suggestion his works were allegorical to the real world he inhabited, it is surely no mistake that Tolkien wrote this chapter after the Second World War. During the rise of Attlee’s welfare state, and what he perceived as the loss of small, local, personal culture and community in favour of impersonal, centralised control. “Shirriffs” patrolling, inns closed, crops seized by officials. Tolkien was describing not just fictional loss but real a personal grief. Sarehole, the rural hamlet of his youth, had become an extension of industrial Birmingham.

His return decades later was a kind of second scouring, this time of his memory. Carpenter quotes Tolkien’s diary:

‘I pass over the pangs to me of passing through Hall Green – become a huge tram-ridden meaningless suburb, where I actually lost my way – and eventually down what is left of beloved lanes of childhood, and past the very gate of our cottage, now in the midst of a sea of new red-brick. The old mill still stands, and Mrs Hunt’s still sticks out into the road as it turns uphill; but the crossing beyond the now fenced-in pool, where the bluebell lane ran down into the mill lane, is now a dangerous crossing alive with motors and red lights. The White Ogre’s house [Tolkien’s nickname for the old miller] (which the children were excited to see) is become a petrol station, and most of Short Avenue and the elms between it and the crossing have gone. How I envy those whose precious early scenery has not been exposed to such violent and peculiarly hideous change.’ (pp. 169-170).

You can picture bluebell lane in spring: flowers in full bloom, the air alive with the humming of insects. It was a secret shortcut home for two rosy-cheeked brothers, counting their mushrooms, the hard-fought spoils of another happy day. Now the air reeks of fumes and throbs with the sound of machinery, and the dead bluebells, along with Tolkien’s childhood memories, lie buried beneath an ocean of tarmac and concrete.

In short he now hated ‘the red-brick wilderness that had once been Sarehole.’ (p. 170).

The speed of the scouring of Sarehole, of the industrial invasion of this once idyll land was unlike anything the world had seen before. As Tolkien put it:

“A person of my age…is exactly the kind of person who has lived through one of the most quickly changing periods known to history… surely never been in seventy years so much change…The world in which I was brought up in as a small child was indefinitely closer to the world of Shakespeare.”

For Tolkien, the beauty of the countryside was more than just a nice place to grow up. It represented a moral goodness: a world ordered around simplicity, community, and harmony with nature. It was anti-machine, anti-Sauron, anti-fascist, even anti-progress. It was an England worth defending. And as we will find out later, it was an England that he defended in more ways than one.

But even more than this, the destruction of the countryside represented to Tolkien a sacral event, an almost divine punishment for the sins of man. It was a loss he struggled to reconcile himself with for the rest of his life. But sadly another loss, equally as potent, was waiting just around the corner.

Click here to travel beyond the innocence of childhood, to lands fraught withdanger, loss, and love.

%20by%20Ivan%20Aivazovsky.jpg)

0 Comments