Why You Shouldn’t Write Like Tolkien (Unless You Are Tolkien) - Part IV

The Morality Of Middle-Earth: Part 1

Blauw Films

Paradise Lost: The Foundations of Morality

The scratching of pens filled the room. Dust drifted in the pale light that slanted through the tall windows, settling on rows of bowed heads and ink-stained fingers. A boy sat at his desk, eyes fixed on the page before him but seeing nothing. The numbers blurred and the master’s voice, droning on about algebra, barely registered. Beyond the glass, a bell tolled across the smokey city, heavy and slow. The mournful sound echoed the grief that filled the boy’s heart so utterly.

*

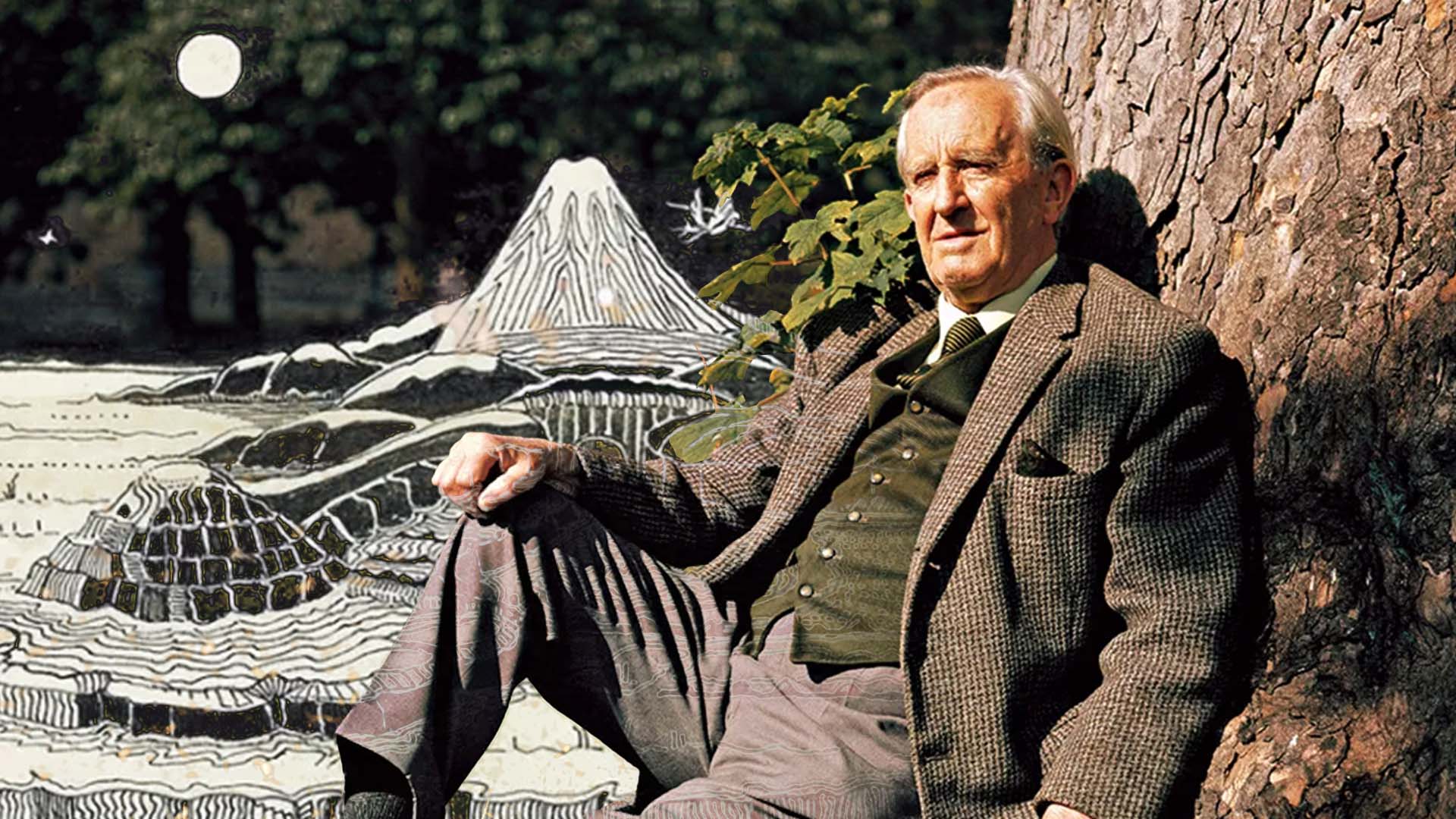

In 1904, Ronald’s beloved mother, Mabel Tolkien, died. She was just thirty-four and Tolkien was only twelve. The early death of his mother, from diabetes, was one of the most significant, defining moments in his young life. Just four years before her death, Mabel had converted to Roman Catholicism, a move that alienated her from much of her extended family. Wyatt North writes, “The passing of his mother in this way colored and deepened his religious devotion forever after, but it also made him aware at an early age of the world’s imperfection and its capacity for death.” (p.18)

Tolkien’s Catholicism was not nominal; as Humphrey Carpenter writes, “any close scrutiny of his life must take account of the importance of his religion. His commitment to Christianity and in particular to the Catholic Church was total.”(p.174) Tolkien had, Carpenter adds, “in this sense a profoundly Christian and ascetic attitude to life.” (p.171)

After her passing, he and his brother were placed under the care of a Catholic priest, Father Francis Morgan, in Birmingham. The bond between Tolkien and Father Francis was deep but this relationship was not the sole driver of Tolkien’s profound faith. It was also forged in grief. Carpenter observes, ‘the loss of his mother had a profound effect on his personality. It made him into a pessimist... More precisely, and more closely related to his mother’s death, when he was in this mood he had a deep sense of impending loss. Nothing was safe. Nothing would last. No battle would be won for ever.’ (pp.50–51)

Even the countryside of his boyhood seemed to betray him after her passing: “Ronald, still numb from the shock of his mother’s death, hated the view of almost unbroken rooftops with the factory chimneys beyond. The green countryside was just visible in the distance, but it now belonged to a remote past that could not be regained. He was trapped in the city… because it was the loss of his mother that had taken him away from all these things, he came to associate them with her.” (p.52)

These early experiences gave Tolkien a moral outlook steeped in the loss of the countryside, his father, and now his mother. This moral outlook, through the lens of hisCatholic faith, led down an inevitable path. A path that led to a life long preoccupation with the Fall of Man.

“If the world were unfallen and man were not sinful, he himself would have spent an undisturbed childhood with his mother in a paradise such as Sarehole had in memory become to him. But his mother had been taken from him by the wickedness of the world”. (Carpenter, p. 170)

In a 1956 letter to his friend Amy Ronald, he confessed: “I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ — though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.”

This “long defeat” theology became one of the central undercurrents of The Lord of the Rings. Tom Shippey summarises it: “The Lord of the Rings can be taken in itself as a myth, in the sense of a work of mediation, reconciling what appear to be incompatibles: heathen and Christian, escapism and reality, immediate victory and lasting defeat, lasting defeat and ultimate victory.” (Foreword)

In Tolkien’s story, Frodo’s quest does not end in unambiguous triumph. In fact, as Tolkien himself admitted, “…where I think I am the most right, is making point of fact that… Frodo actually failed.” At the brink of Mount Doom, he claims the Ring for himself, and only the sudden, almost absurd intervention of Gollum, biting off Frodo’s finger and tumbling into the fire, brings the quest to its conclusion. This is no act of human mastery, but something more mysterious: what Tolkien in his essay On Fairy-Stories called the “sudden and miraculous grace” of eucatastrophe:

“In its fairy-tale – or otherworld – setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure… it denies… universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

The providential role of Gollum, so unlikely yet so necessary, mirrors the Catholic belief in divine providence working through even the most corrupted of wills. A reminder that redemption often comes in ways no hero can plan. Frodo’s failure, the fading of the Elves, and the rise of the Age of Men mean there are no simple “happy endings” in Tolkien’s world. Only those fleeting, grace-filled moments Tolkien describes. This was a moral framework that was sober, unsentimental, and, as Tolkien once claimed, “entirely stoically minded.” (Though, as anyone who has read his his work can attest to, that is perhaps a self-deception of a man who was so evidently romantic and emotional.)

Tolkien’s moral vision was therefore never one of easy victories or moral clarity. It was, as he told Amy Ronald, the acceptance of “a long defeat,” with the hope, but never the guarantee, of the redemption of grace. His Catholic imagination held in tension the sorrow of the Fall and the joy of redemption, (just as his beloved northern myths held in tension heroic courage and inevitable loss, which we will examine in a later post).

This is why, even when Middle-earth is at peace, the shadow never truly departs. Frodo cannot remain in the Shire; the Elves must sail west; the world of magic and wonder recedes into memory. For Tolkien, this was not cynicism but a recognition of how history and the story of Christ works. A cycle of rise and fall, renewal and decline, where victoryis always partial, fleeting, and never inevitable for mortal men. And yet, like the faint light of Eärendil shining in Mordor’s darkened sky, the hope of grace can always persist.

%20by%20Ivan%20Aivazovsky.jpg)

0 Comments