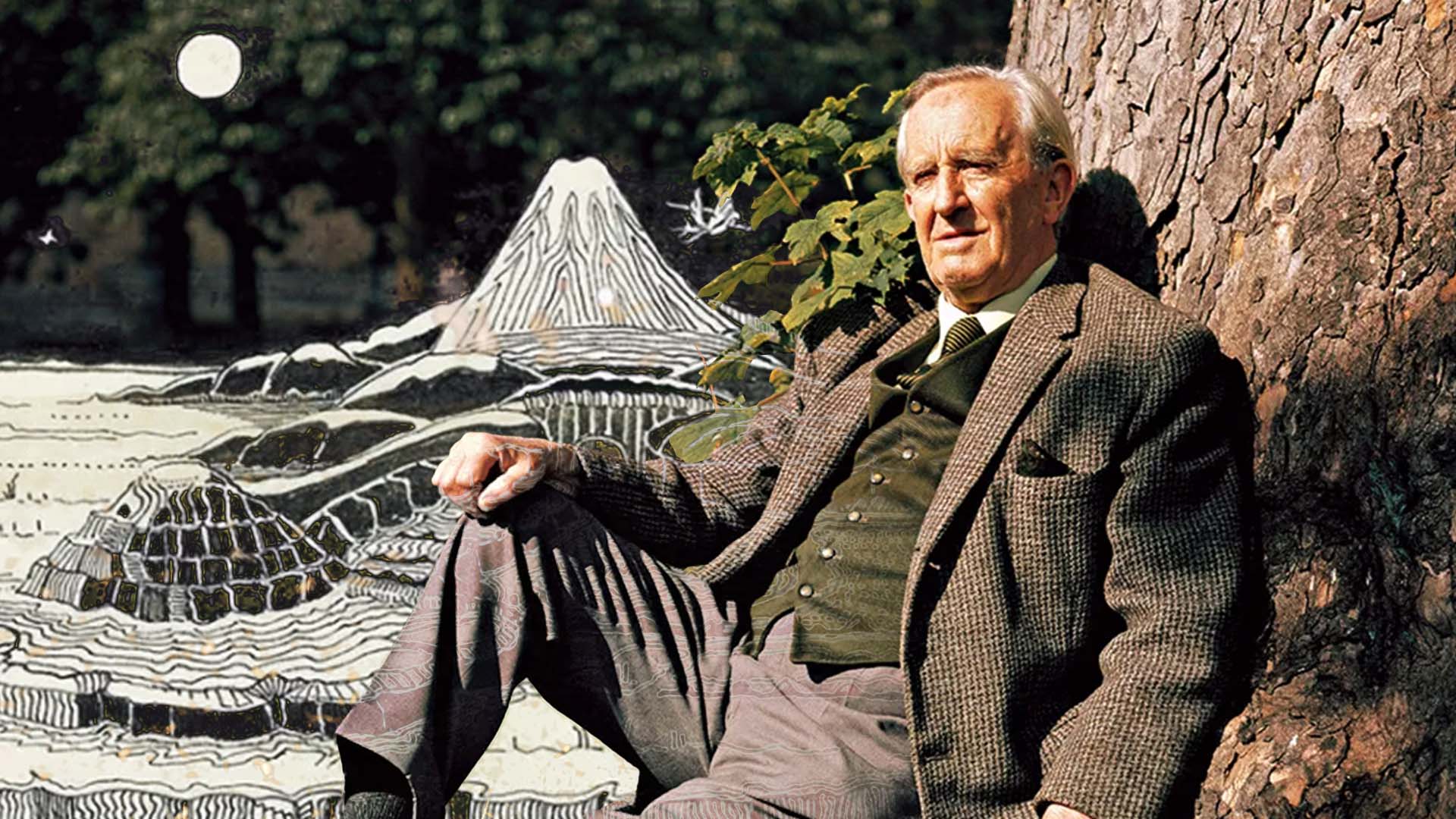

Why You Shouldn’t Write Like Tolkien (Unless You Are Tolkien) - Part V

The Morality Of Middle-Earth: Part 2

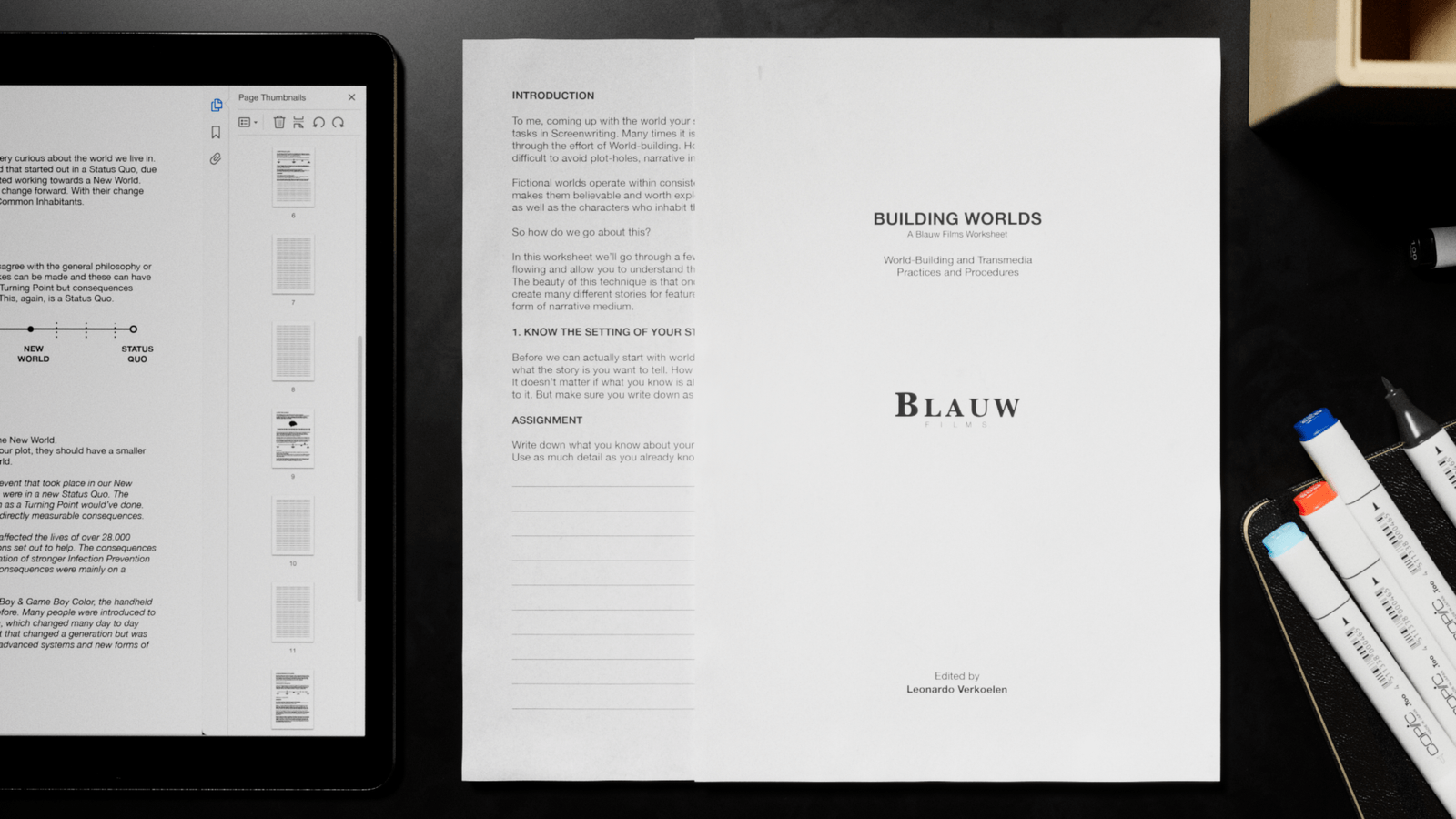

Blauw Films

A Christian Tale: Aslan and Allegory

The hushed chapel was filled with the faint scent of incense and the glow of candles flickering against the stone walls. A boy sat on a pew, his hands crossed on his lap, and his head bowed. Even though he understood the Latin sermon spoken from the pulpit by Father Morgan, he allowed the music of the language to wash over him. His faith in God lay in just that... in the word ‘faith’. Fides in Latin. Fidelity. Trust. Faith. If he was to understand, to truly understand, the mysteries of God’s will, then there would be no reason to have faith in the first place. It was in the unspoken, unknown, unknowable mystery that he found peace.

He pulled the kneeler from the hook in front of him and lay it on the stone floor. He slowly lowered himself to his knees and rested his elbows softly on the pew in front. He clasped his hands and closed his eyes and, bathing in the slow, steady, rhythm of Father Morgan’s voice, he allowed himself to sink deeper, deeper still, into the depths above.

*

“I dislike allegory, whenever I smell it.”

Tolkien’s distaste for allegory was not a passing irritation. It was one of his most frequently repeated literary principles. In the foreword to The Lord of the Rings, he fervently declared:

“I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers.” (p.253)

Tolkien himself rejected the idea that the moments that smelt like allegory were “allegory” for Christian doctrine. He instead preferred the idea of applicability. As Tom Shippey notes, the distinction is crucial: allegory is prescriptive, demanding the reader decode symbols and meaning in a fixed way; applicability is permissive, allowing the reader to draw their own moral or spiritual resonances from the work.

His faith however would be present in another way, not as an explicit sermon, but in the deep moral grammar of the world he created. Like his faith in God the meaning in his work lay in the mysterious depths and not on the surface, like in his contemporary and friend, C.S. Lewis’s, The Chronicles of Narnia.

Yet even though Tolkien wished readers to draw their own meaning from his work, that is not to say he did not consciously include religious ideas: Tolkien told a correspondent in 1953:

“The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously at first, but consciously in the revision.”

Shippey points to one example of this subtle embedding: the Ring’s destruction on March 25, a date loaded with Christian significance. Gandalf tells Sam: “in Gondor the New Year will always now begin upon the twenty-fifth of March when Sauron fell, and when you were brought out of the fire to the King." This is ‘also the date of the Fall of Adam and Eve, the felix culpa whose disastrous effects the Annunciation and the Crucifixion were to annul or repair.’ (p.208).

Unlike his friend C.S. Lewis, Tolkien would never place an overtly Christ-like-figure at the centre of his story. Yet although there is no exact Christ figure in The Lord of the Rings, Frodo comes closest. Shippey cautions, however: “It would be quite wrong to suggest that he is a Christ-figure, an allegory of Christ… Yet he represents something related: perhaps, an image of natural humanity trying to do its best in native decency, trying to find its way from inertia (the Shire) past mere furious heroic dauntlessness (Boromir and the rest) to some limited success.” (p.187). Although it is not a direct allegory its seems to me that Frodo’s journey seems to reflect (albeit in a smudged and tarnished mirror), the struggle of Christ, or perhaps the struggle of man. Whatever you take away from it, it is clear that there are Christian undertones buried deeply in Tolkien’s work.

These undertones were shaped in part by his friendship, and disagreements, with C.S. Lewis. Wyatt North notes that “Tolkien and Lewis were actually quite suspicious and wary of one another… but before long their mutual interest in writing, mythology, and religion drew them together.” (p.55) Their theological imaginations diverged sharply in method. Lewis, in The Chronicles of Narnia, presented Aslan as an unmistakable Christ figure. Tolkien found such directness heavy-handed: “Allegory… is coercive, forcing the reader to see things in a certain way.” (p.82) In his view, myth, not allegory, was the more subtle and powerful vehicle for truth.

So what is this truth? This truth that is a fundamental part of Catholicism and so utterly shaped Tolkien’s worldview?

At the heart of his fiction lies a theme central to Catholic thought: death and mortality. As Tolkien himself put it, “Stories – frankly, human stories are always about one thing – death. The inevitability of death.”

Before we travel to the muddy marshes of death click here to enter a certain glade in a certain wood, where hemlock grows and love blooms.

%20by%20Ivan%20Aivazovsky.jpg)

0 Comments