Why You Shouldn’t Write Like Tolkien (Unless You Are Tolkien) - Part VI

The Morality Of Middle-Earth: Part 3

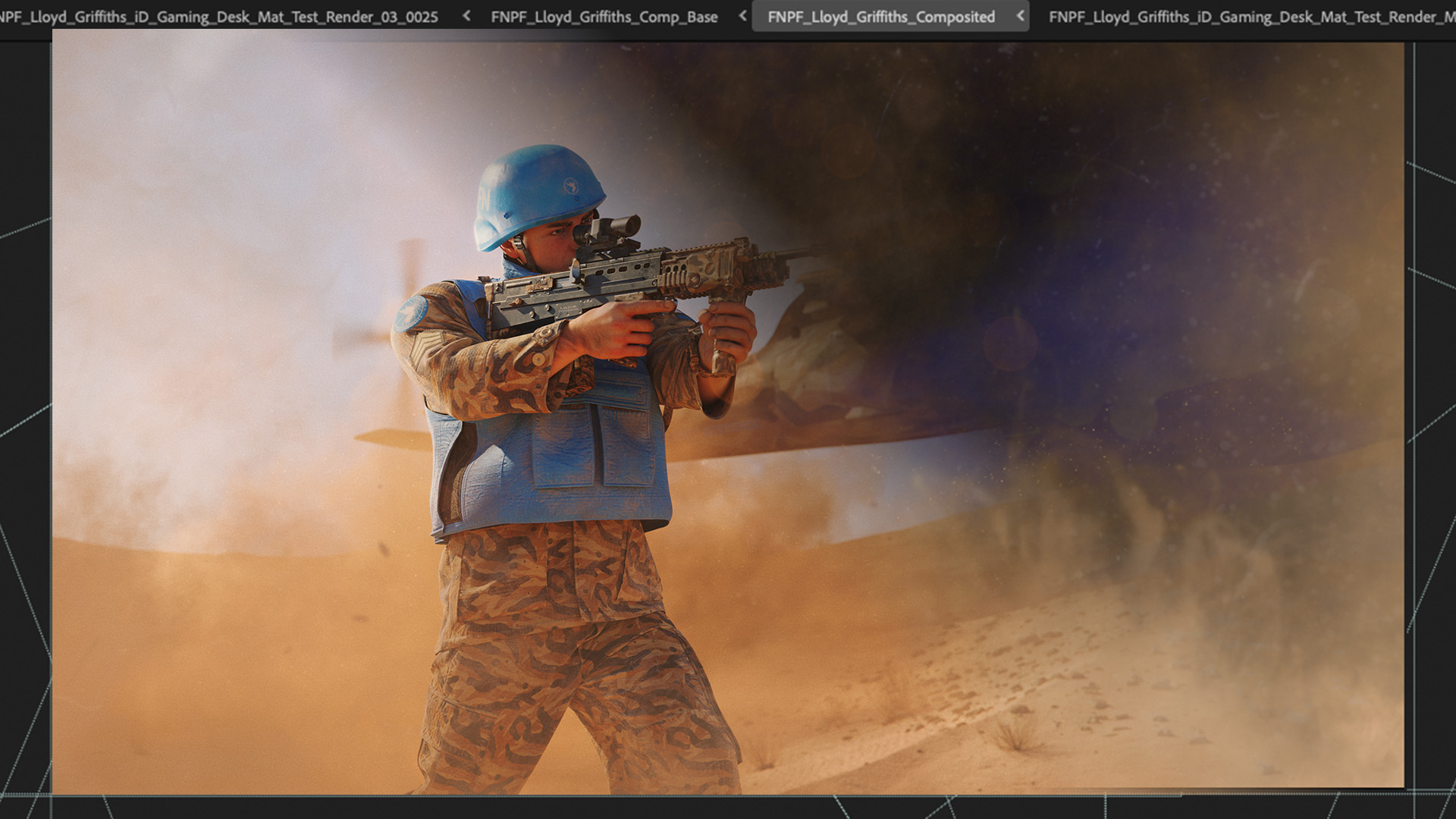

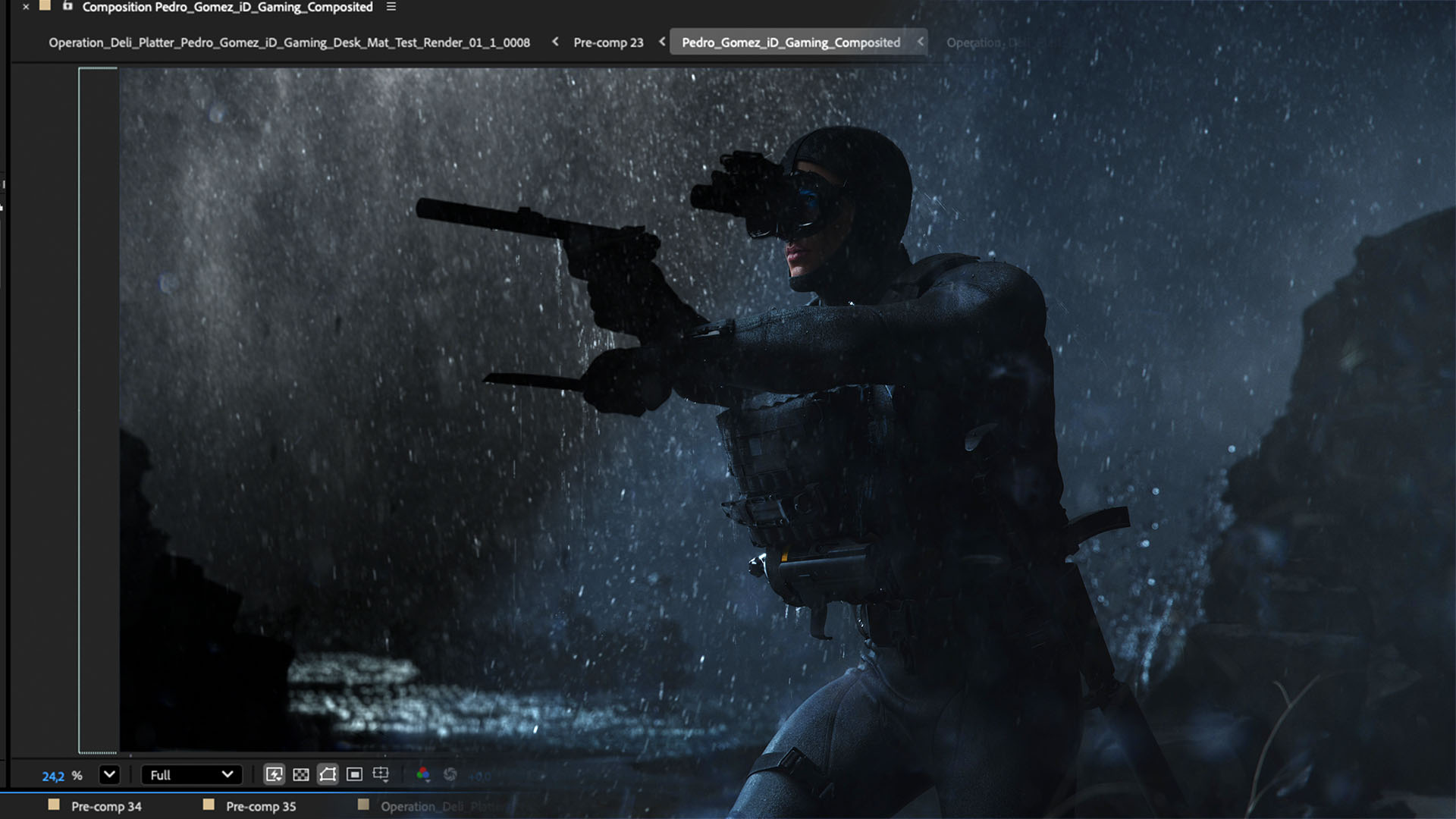

Blauw Films

The Tale of Edith: Love and Lúthien

He had almost died, but when he thought about it, he supposed he was one of the lucky ones. The worst of the trench fever was behind him, and the summer lay ahead. He found himself strolling through the Yorkshire woodland, arm in arm with her. They were as far from the banks of the River Somme as it was possible to be. Spring had well and truly sprung, and the ground was awash with flowering herbs, their scent thick on the clear air.

Before long they came upon a small glade where white hemlock swayed in the breeze. She stepped ahead, her hand brushing the flowers, and then she turned to him, smiling. Without a word she began to dance, light-footed and laughing, her dark hair alive in the sunlight. The love he had felt since he was a boy rose within him, and in that moment the world was whole again. Yet as he watched this divine apparition dance, a deep sorrow overwhelmed him. Soon he would be forced to return, to go back to France, back to the trenches, back to war. He was unlikely to see another Christmas. The inevitability of his impending death struck him. He was a mere mortal in the presence of an immortal nymph, whose life, compared to his own, stretched out before her into the far-flung reaches of eternity.

*

The other great pillar of Tolkien’s life was his love for Edith Bratt, three years his senior. They first met while boarding in the same house in Birmingham. Tolkien, then only sixteen, was utterly captivated by her. His guardian however, Father Francis Morgan, disapproved, believing the relationship might distract the young scholar from his studies. “Father Francis requested that Ronald not write to her until he was twenty-one” (North, p. 20). Most teenagers might ignore such an order, but Tolkien, like a pious hero who might have stepped straight out of one of his own books (of perhaps just a timid Catholic boy doing as he was told) accepted the quest with stoic resolve. So he waited.

When the day finally came, and war loomed on his horizon, he wasted no time. “Ronald and Edith decided to marry before his departure, knowing full well that he might not return” (North, p. 34). He went off to the front to fight in the Great War (which we will get to later). In 1917 he was forced home by an illness and while recovering in Thirtle Bridge, near the village of Roos on the east coast of England, he was well enough to go for a walk with Edith in the woods nearby.

It was late spring, and summer was stretching her legs. On that day, “Edith sang and danced, looking more beautiful than ever before to him” (North, p. 45). It was there in those woods, in that joyful moment that one of The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion’s greatest themes was born: mortality. Humphrey Carpenter records that “from this came the story that was to be the centre of The Silmarillion: the tale of the mortal manBeren who loves the immortal elven-maid Lúthien Tinúviel, whom he first sees dancing among hemlock in a wood” (Carpenter, pp. 135–136). Tom Shippey notes that “the story of Beren and Lúthien remained deeply personal to Tolkien till he died: he had the names ‘Beren’ and ‘Lúthien’ carved on his and his wife’s shared tombstone, a striking identification” (Shippey, p. 247).

In the legendarium, Lúthien “escapes from deathlessness, for she, like Arwen in Appendix A of The Lord of the Rings, is allowed to choose death and finally accompany her husband” (Shippey, p. 248). The story captures one of the central tensions in Tolkien’s mythology: Men are mortal, while Elves are immortal. Men can change, grow, falter, strive and die; Elves are bound to the world until its end, their fate a kind of stasis. Immortality, Tolkien came to believe, is not a gift but a burden. “One might argue,” Shippey suggests, “that Tolkien, elaborating his stories of a race choosing the fate of mortality, was trying to persuade himself that mortality had after all some attractions, invisible though those might be to humans who have no other choice” (pp. 248–249).

That reflection on mortality was never far from his mind, even in his most blissful moments. The inspiration he took from Edith’s dance was not only a vision of beauty and life but also of loss and death. This was not morbid sentimentality, it was a deep awareness that love, however enduring, is framed by mortality.

And soon, the shadow of mortality would loom closer still. The young officer who had waited years for his beloved would be forced to return to a world at war, where death was not a mythological theme, but a daily, choking reality.

.jpg)

%20by%20Ivan%20Aivazovsky.jpg)

0 Comments